Lessons from Abroad

Sean Gammons is a director for NERA’s European Energy Group and specializes in economic and valuation issues in the power and gas industries. In his advisory work he specializes in market analysis and regulation for corporate and government clients.

Glenn George is a senior vice president in NERA’s Global Energy, Environment, and Network Industries Practice, where he advises clients on the economics of electric power, natural gas, and related markets as they evolve in response to political, regulatory, and technological change. He has three decades of experience in the global energy sector as an engineer, policymaker, entrepreneur, investment banker, economic consultant, regulatory expert, and strategist. He advised the Government of Japan on the new electric power market rules which went into effect in April of this year. Dr. George holds an engineering degree and an MBA, both from Cornell University; a PhD from Harvard University, with a focus on regulatory economics; and is a registered Professional Engineer in the District of Columbia.

Robert Southern is the head of NERA’s Australian offices. He has extensive experience in the provision of public policy, economic, financial, and related advisory services in Australia, Asia, and the Pacific region.

Willis Geffert is a Senior Consultant in NERA’s Energy, Environment, and Network Industries Practice, specializing in sophisticated economic analysis and modeling to assist global energy clients in meeting the strategic, financial, and legal challenges of operating in restructured and regulated markets. He has extensive experience in European and North American power markets, including Ireland’s SEM, Russia, PJM, NYISO, CAISO, and New Brunswick in Canada.

Japan has a long history of direct foreign investment across a wide range of industries and sectors globally, especially natural resources and industrial goods.

The strategies underpinning those investments are many and varied. They include securing supplies of input materials, and decreasing the cost of labour and transportation to make goods more competitive. They also include gaining access to key technologies for potential redeployment in the home market.

There is yet another strategy underpinning Japanese direct foreign investment in overseas energy-sector assets. This includes gaining experience in restructured energy markets globally so as to thrive in the newly liberalized power market back home in Japan.

This article explores this phenomenon in the context of Japanese experience investing in the energy sector of the U.S., Mexico, the U.K., and Australia.

U.S. Experience

1. Background

In December 1980, the government of Japan passed a Foreign Exchange Control Law, which significantly reduced controls on capital outflows. Japanese companies previously made small direct investments in the U.S. This new law, combined with a stronger Yen, unleashed a wave of Japanese investments overseas, especially in the U.S.

Japanese companies invested in a number of sectors, including real estate, finance, entertainment, and industrial firms. Energy-sector investments were not far behind.

2. Investment Profile

Japanese companies have pursued a number of distinct strategies through their U.S. energy-sector investments over time. These include the following:

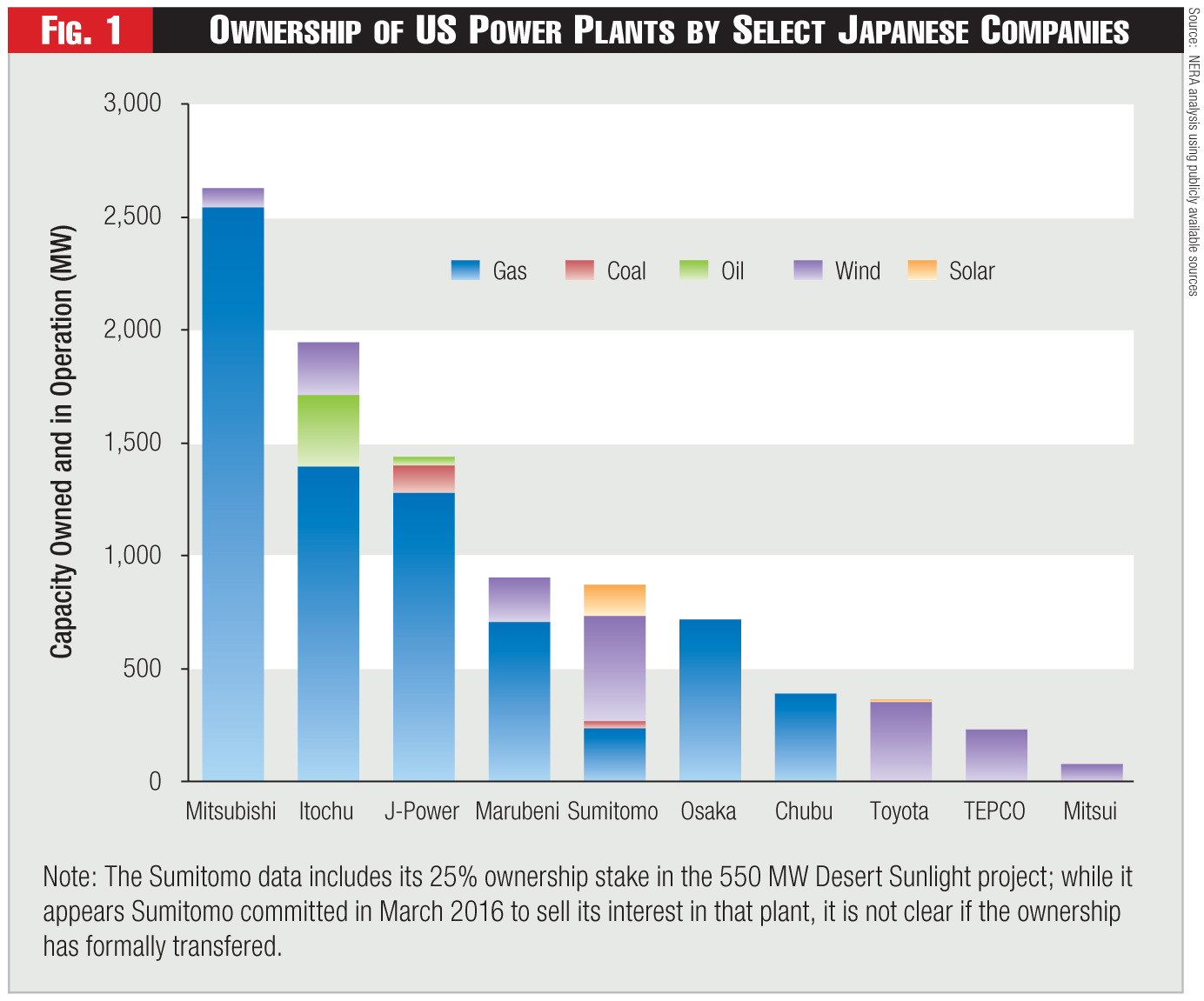

Renewables: As a result of incentives created by the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978, Japanese companies initially invested in renewable assets. This preference has generally continued until the present.

Toyota Tsusho, for example, invested relatively early. In the late 1980s, twenty years before some of its competitors, Toyota Tsusho invested in a wind power development in the Mojave Desert in California. These wind and solar investments are now held in an entity called Eurus Energy, itself owned sixty percent by Toyota and forty percent by Tokyo Electric Power Company. 1

Sumitomo has joined Toyota and Tokyo Electric as a renewable-sector leader. Sumitomo has invested in about two thousand megawatts of wind and solar capacity, actually owning about a quarter of those plants.

Sumitomo’s portfolio includes investments in multiple high-profile projects, such as an eight hundred forty-five megawatt wind farm in Oregon, at one time the world’s largest. It also includes the five hundred fifty megawatt Desert Sunlight Solar Farm, the largest photovoltaic facility on U.S. federal land. 2

Independent Power Plants: With development of competitive power markets in the mid-1990s through the early-2000s, Japanese companies began investing in independent power plants, generally fossil-powered. For example, Osaka Gas has acquired minority interests in already operating thermal plants. That began with its purchase in 2004 of a forty percent interest in the eight hundred forty-five megawatt Gateway combined-cycle station in Texas.

While many Japanese companies have followed the Osaka Gas model of investing in existing power plants, some have invested in new capacity. Marubeni, for example, was an early participant, pre-financial close, in a seven hundred twenty-five megawatt combined-cycle plant currently under construction in Maryland.

J-Power generally owns all, or at least a majority, of its U.S. generation assets. This is in contrast to the Japanese trading companies and utilities, which tend to hold minority interests.

Japanese companies have invested across the U.S., gaining exposure to various restructured and regulated markets.

Figure 1 summarizes the current U.S. power plant ownership of several large Japanese companies.

Operation and Maintenance: Overall, most Japanese companies do not operate the plants in which they have invested. 3 Nonetheless, a few companies have made power-plant services an important part of their business. 4

In 2001, for example, Itochu purchased Dynegy’s operation and maintenance services company, North American Energy Services. The company was the largest third-party provider of those services to independent power plants. Then, in 2003, Itochu invested in Tyr Energy, now a generation company. At that time, it focused on management services to the owners of merchant power plants. 5 Marubeni also acquired the PIC Group, a generation services company. 6

Nuclear: Japanese companies invested in the U.S. nuclear sector. This was due to the advent of the nuclear renaissance beginning in the early-2000s, with an added impetus from the nuclear power incentives in the Energy Policy Act of 2005.

Mitsubishi provides various nuclear services, and has developed an advanced reactor design, the advanced pressurized water reactor. 7 Mitsubishi also supplied replacement steam generators to the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station, before it was permanently shut down in 2013 due to tube leaks in the steam generators.

Toshiba purchased Westinghouse, the developer of the AP 1000 nuclear technology. Four such units are currently under construction in the U.S. and many more are under construction in China. Marubeni owns Energy U.S.A., Inc., a uranium trader and a provider of various consulting, financial, and equipment services to nuclear plants and uranium companies.

Natural Gas Value Chain: Japan is almost completely dependent on gas-fired generation, post-Fukushima. Following the accident, nuclear plants shut down throughout Japan, perhaps permanently, and thus a number of players have moved up the natural-gas value chain. They have moved from liquefied natural gas export terminals, up to exploration and production assets, in an effort to secure supplies.

For example, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Nippon Yusen, Tokyo Gas, Sumitomo, and Osaka Gas participate in new liquefied natural gas export projects in the U.S. These include the Cameron (Louisiana), Freeport (Texas), and Cove Point (Maryland) terminals. Several Japanese companies are considering this export potential in British Columbia, as well.

On the exploration and production side, Mitsui has invested in Marcellus shale gas in Pennsylvania, and in Eagle Ford shale oil and gas in Texas. Osaka Gas, Marubeni, and Tokyo Gas also participate in Eagle Ford projects. Other U.S. shale investments include Sumitomo in Wolfcamp, Marubeni in Niobrara, and Tokyo Gas in Barnett.

Next Frontier Technologies: Japan has an eye on development of energy storage, distributed generation, small-scale renewables, microgrids, and related technologies. Some Japanese companies have begun to focus on these elements in the value chain.

Mitsui, which has just a small presence in U.S. independent power plants, recently invested in Stem, Inc. It is a company focusing on distributed services, including storage, demand response, and advanced information technology controls.

3. U.S. Lessons Learned

Although Japanese investment in the U.S. energy sector continues to unfold and evolve, a few general lessons can be discerned. Sometimes the next best thing fizzles before the investment pays off, with new nuclear power in the U.S. a prime example of this phenomenon.

Some countries, like the U.S. – due to their devolved or federal political structure – are not a single market. Rather, they are a series of lightly-connected regional or local markets, each with a very distinctive character. One investment strategy clearly does not fit all regions or sectors, even in a single country.

From the perspective of learning how liberalized energy markets function, some of the most promising strategies have been little-pursued to date. These include investing in regulated utility companies in order to gain direct experience. These strategies may be ripe for more active deployment.

Mexico Experience

1. Background

Japanese companies have invested in the Mexican power sector since the Law of Public Electricity Service was reformed in 1992. This opened up the sector to private capital investments. In fact, the Japanese trading company Sojitz was a minority participant in the first independent power plant bid following that reform, awarded in 1997. Japanese companies were also among the first successful bidders in build-lease-transfer projects under the new legal regime.

Prior to the 1992 legislation, Comisión Federal de Electricidad, or CFE, owned, controlled, and operated basically the entire electricity sector, as a state-owned vertically-integrated monopoly. 8 The 1992 legislation opened up the sector to private investment, under multiple modalities.

These include independent power plants, build-lease-transfer projects, co-generation and self-supply, 9 small power plants, and import and export permits. CFE’s dominance, however, continued.

CFE remained in charge of system planning. It also remained involved as the off-taker in standard contracts issued to independent plants. In addition, it is the lessee of the build-lease-transfer projects, which are transferred to it after the lease.

Large customers, however, could purchase power directly from privately-owned self-supply or co-generation plants. While further reforms of the sector proposed in the 1990s ultimately failed, Mexico enacted a new Electricity Law in 2014.

Highlights of this latest cycle of reform include the following:

- Splitting Up CFE Vertically: The wires business with separate transmission and distribution subsidiaries will be independent from generation. This, in turn, will be separate from the retail business. 10 An independent system operator has already been formed.

- Splitting Up CFE Horizontally: Its generation assets will be split into several generating company subsidiaries. Their mission is to operate as independent, profit-maximizing concerns.

- Opening the Market to Competitive Retail Suppliers.

- Establishing Competitive Mid- and Long-Term Auctions to Procure Energy, Capacity, and Clean Energy Certificates. 11 Also, establishing a wholesale power market,with a day-ahead and real-time market, as well as a capacity market. 12

2. Investment Profile

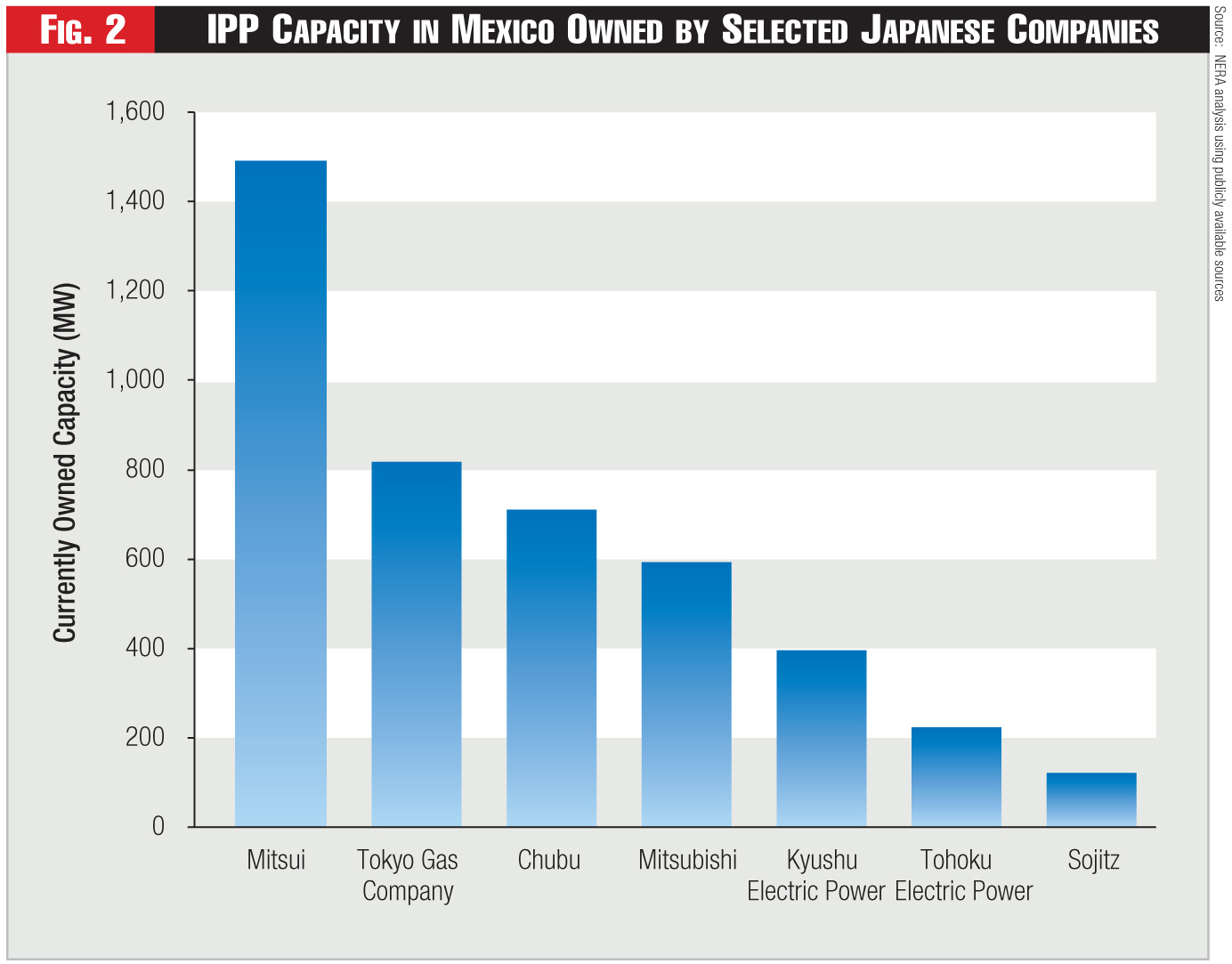

Mexico has been and remains a high-growth market for electric power and other forms of energy. From 1992 to 2013, electricity consumption grew one hundred twenty-two percent, contrasted with twenty percent growth in Japan over that same period.

From 2013 to 2029, electricity consumption is expected to grow by about an additional sixty percent, or about three percent per year. 13 Projected growth is somewhat slower than historical levels. It is, however, quite robust when compared with the U.S., where consumption is expected to grow about half a percent per annum during the same period. 14

Further, the generation mix in Mexico is rapidly changing. It is transitioning from a system traditionally dominated by nuclear, hydro, coal, and oil or dual-fueled steam turbines. The system is now shifting to one dominated by combined-cycle units and renewables. The renewables include wind, solar, and hydro. The system may also transition to additional nuclear.

Significant steam turbine and coal capacity is scheduled to retire in the coming years. In sum, significant new capacity will be required. Japanese investments have provided a significant portion of new capacity in Mexico over the last two decades, through various strategies: 15

Developing Independent Power Producers: Whether as minority or majority investors, Japanese companies have won numerous competitive solicitations by CFE to build, own, and operate independent power plants in Mexico. These plants come with twenty-five year contracts with CFE as off-taker, where afterwards the companies are free to sell their plants’ output to third parties.16

Mitsubishi, for example, has won multiple independent power producer solicitations, partnering with Kyushu Electric Power or with Électricité de France. And Sojitz participated and won as a minority partner in an independent producer solicitation.

Investing in Independent Power Producers Already Awarded:Several Japanese companies have employed this strategy, including Chubu Gas, Mitsui, Tokyo Gas, and Tohoku Electric Power. So far, all such plants owned by Japanese companies are combined-cycle units.

Figure 2 shows current ownership of independent power producers in Mexico by company. 17

Build Lease Transfer Projects:In addition to offering competitive bids for independent producers,CFEbid out several other projects on a build lease transfer basis. In this arrangement, the winning bidder finances and builds the plant. It then leases the plant to CFE for long-term operation and transfers ownership when the lease expires. Mitsubishi has frequently been successful in these bids.

Self-Supply and Co-Generation Plants:Under this scheme, investors obtain a permit from Mexico’s Energy Regulatory Commission to build power plants. Then they sell their output under contract directly to large customers that became their partners.

This scheme has grown rapidly since the opening up of the sector in 1992. Participating Japanese companies include Mitsui and Mitsubishi, with both companies having built wind projects.

Variation on the Self-Supply Strategy: In a variation on the self-supply strategy, investors can size their independent power plants larger than the CFE off-take contract, then sell the residual to large customers. Tokyo Gas purchased a minority stake in a provider that follows this strategy.

Under the 2014 law, power plants will be built under generator permits and may sell their products under different schemes. Japanese companies have not yet invested under the new law.

3. Mexico Lessons Learned

Japanese companies investing in Mexico are likely to learn more valuable lessons to bring back to Japan during the coming years than were learned in the last two decades. In Mexico, Japan has a preview of how a new power market design is implemented. It’s perhaps a few years before reform reaches a similar stage in Japan.

Japanese companies will see the challenges markets can have in their early years. Potential learning opportunities include the following:

Observing: Even companies which only maintain existing contracts under the old rules can still learn from their front row seat to the new market. 18

Participating in Competitive Procurement Mechanisms: In Japan, the new grid operator, the Organization for Cross-Regional Coordination of Transmission Operators, may run capacity auctions. Long-term auctions are already occurring in Mexico. Medium-term auctions may follow.

Building Merchant Capacity: Of course, there are significant risks in this strategy, not the least because there is currently a glut of capacity in Mexico. As older, less efficient units retire, a need for additional capacity may develop.

A company may decide not to build. Exploring the option through price forecasting, risk assessment, and contractual mechanisms, however, would provide valuable experience. This could be redeployed back in the home market.

Becoming a Competitive Retail Supplier: Learning how to become a competitive retail supplier in a market like Mexico could create bona fide capabilities to support new lines of business over time in Japan. This approach is not without its risks.

U.K. Experience

1. Background

The U.K. shares some similarities with Japan in terms of overall economic conditions. It is a large island state with an advanced industrial economy. The economy is highly dependent on the availability of a secure and affordable electricity supply.

The big underlying difference between the two countries is the availability of indigenous fuel resources. The U.K. is fortunate in having access to domestic coal, gas, and oil resources, unlike Japan.

In terms of the organization of the power sector, the key difference to date has been the U.K.’s much greater appetite for competition. Along with a few other markets around the world, the U.K. has been at the forefront of the development of competitive electric power markets. These other markets include Norway, New Zealand, and those U.S. states that have unbundled their electricity sector.

Indeed, the U.K. has arguably gone further than any other market towards the development of full and effective retail competition. The process of development of competition in the U.K. has been far from smooth and the results are contested. At a high level, two phases are discernible:

An early period extending from 1989-90 to about 2005 of deregulation and increasing reliance on competition and market prices (“competition in the market”) as a means of promoting efficiency and security of supply, whether in generation, retail or low carbon investment. This period was characterised by dramatic shifts in market structure and falling prices, partly as a result of benign international fuel markets.

A later period extending from about 2005 to the present day of growing doubts over the efficacy of free markets (in particular for decarbonisation) and a trend of re-regulation, whether in the form of an explicit auction market for generation capacity, or increasing regulatory interventions in retail, or the move to long-term contracts, known as Contract for Difference – Feed-in Tariff (CfD-FiT), for low carbon investments. This period has been characterised by a much more stable market structure, a move to greater use of centralized procurement (“competition for the market”), and rising market prices, partly as a result of rising international fuel prices and partly due to increased costs of environmental regulation.

In summary, the initial burst of enthusiasm for competition in the U.K. has given way to a new round of regulatory intervention that is changing the nature of competition, and possibly threatens the sustainability of a competitive electricity market. Legacy assets, whether owned by the U.K.’s so-called “Big 6” energy companies or independents, have generally suffered as a result of this switch in policy-making – margins have been squeezed and heightened regulatory risk has driven down asset values. New opportunities have arisen, however, in particular for investments in low carbon generation under long-term Contract for Difference – Feed-in Tariffs that offer the prospect of returns that are shielded from the vicissitudes of regulatory change.

It is in this challenging environment that Japanese investment in the U.K. power sector has been made.

2. Investment Profile

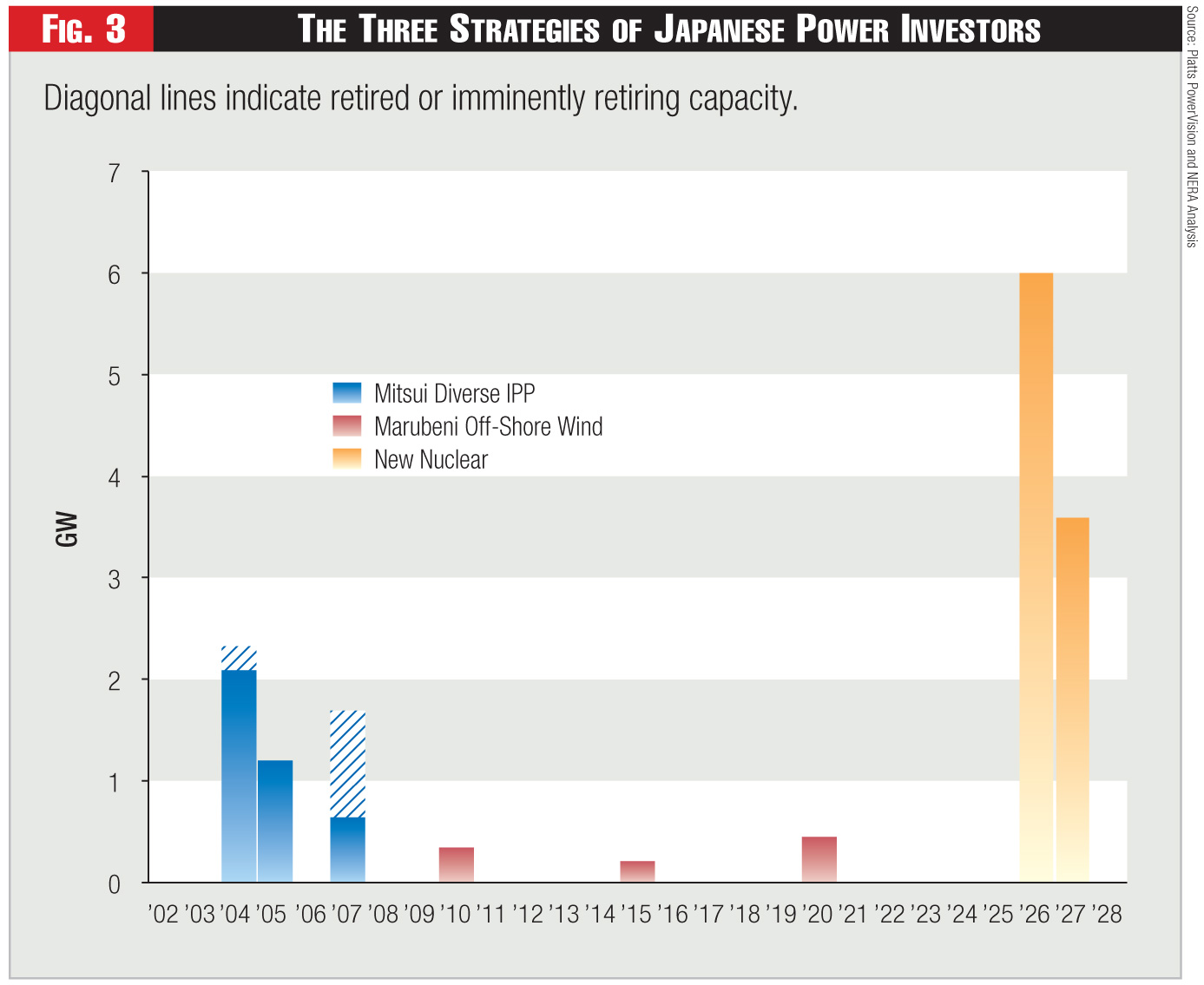

Cumulatively, Japanese investment in the U.K. power sector (in operating assets and projects in development) totals approximately sixteen gigawatts of plant capacity. See Figure 3.

Japanese investors have employed three main strategies in the U.K. power market to date:

Diversified Merchant Independent Power Producer: Mitsui has built minority stakes in operational largely-merchant assets in partnership with an incumbent independent power producer. Between 2004 and 2005, Mitsui acquired stakes in approximately fourteen hundred megawatts of gas plant and twenty-one hundred megawatts of pumped storage. In 2007, Mitsui swapped shares with their partner for a stake in over a thousand megawatts of coal, gas, and oil plants. Subsequently, part of the portfolio has been retired or has been tagged for retirement. In April 2016 Mitsui put its remaining stake up for sale.

Quasi-Regulated Offshore Wind: Marubeni has participated in the development of offshore wind farms in the U.K. via minority stakes. Its first investment, in 2011, in partnership with the Development Bank of Japan and others, was in the Gunfleet Sands wind farm, operational at around one hundred seventy megawatts. This was supported by the Renewables Obligation green certificate system that pre-dated the new Contract for Difference – Feed-in Tariffs contracts.

It followed up in 2014 with the acquisition of a stake in the Westermost Rough wind farm, with commissioning of over two hundred megawatts taking place the following year. This was also supported by the Renewables Obligation. Through its minority stake in Mainstream Renewable Power Ltd., which it acquired in 2013, Marubeni also has interests in the development of the Neart na Gaoithe wind farm, where it is also one of the construction contractors. It is off the shore of Scotland, with capacity of four hundred fifty megawatts. It is due to be commissioned in 2020 under a Contract for Difference – Feed-in Tarriffs contract.

Quasi-Regulated, New-Build Nuclear: Initially the domain of Big 6 energy companies, 19 two of the three consortia of new nuclear developers in the U.K. are now majority Japanese-owned. Horizon Nuclear Power was purchased by Hitachi from RWE and E.On. It plans to build two plants of three thousand megawatts by 2026. In partnership with Engie as part of NuGen, Toshiba is developing a thirty-six hundred megawatt plant, slated to come online in 2027. All these projects are targeting long-term Contract for Difference – Feed-in Tarriffs contracts.

3. U.K. Lessons Learned

The Japanese investors who have invested in the U.K. power sector have learned a great deal about investing in liberalized power markets. This experience will position them well to participate in the development of competition in Japan.

For example, Mitsui now has a wealth of expertise in power trading and the value creation opportunities it offers when allied with optimization of physical generation. And Marubeni, Hitachi, and Toshiba have developed regulatory expertise in how to organize low-carbon generation investment in a liberalized environment with changing regulation.

More generally, several lessons can be distilled from experience of the U.K power sector:

Competition takes different forms (“competition in the market” versus “competition for the market”) and the regulatory authorities’ preferences for one over the other may shift over time.

Shifts in underlying fundamentals, whether in terms of fuel prices or the availability of technology or environmental regulation, are likely to be correlated with calls for reform of regulatory arrangements.

Regulatory constraints are at least as important as market fundamentals in creating investment incentives and in determining the risks and rewards associated with a given investment.

Merchant assets are particularly exposed to regulatory change as compared to long-term contracted assets.

Australia Experience

1. Background

Over the past decade, Japan has consistently rated as the third-largest investor in Australia, measured by value of foreign direct investment. During this period, a substantial proportion of that investment has been in the energy sector. This includes approximately eleven percent in coal, oil, and natural gas.

Japanese investors have faced a number of very significant changes over time in the regulation and operation of the Australian National Electricity Market. These dynamics have meant that Japanese and other investors have needed to manage a range of factors, including the following:

Regulatory Uncertainty:The past decade has seen the establishment of the Australian Energy Regulator. It has seen the transfer of regulatory responsibility from state governments to the federal government. In addition, it has seen changes to the national electricity rules, and the regulatory framework under which they operate. This process entailed disruption and growing pains as utilities learned to deal with a new and different regulator.

Introduction of Full Retail Competition: Full retail competition has been gradually introduced across the National Electricity Market. Victoria and New South Wales initially moved to full retail competition in the early 2000s. All other states introduced full retail competition by 2014.

Change in National Energy Market Governance Arrangements: In the early 2000s there was substantial change to the governance arrangements of the originally established governing bodies. These include the National Electricity Code Administrator and National Electricity Market Management Company Limited.

The Australian Energy Market Commission was established as the rule-maker and policy adviser on the National Energy Market. The Australian Energy Regulator was formed as the national regulator. Later in 2009, the Australian Energy Market Operator was established to oversee operation of the electricity and gas markets in Australia.

Change in Industry Structure and Ownership: The electricity industry in Australia was, by and large, vertically separated in the 1990s. There has been an increasing trend of vertical integration in the competitive generation and retail segments of the market.

Gentailers emerged, which are a combination of generators and retailers.

Gentailers have used their unique position in the value chain to manage risk flowing from price volatility in the wholesale energy market. This has not necessarily resulted in decreased competition. There has been a trend of new entrant retailers or generators entering as gentailers.

2. Investment Profile

The majority of Japanese investment in the Australian energy market has been in the natural gas and liquefied natural gas processing sectors. There has also been substantial investment in electricity generation and electricity network assets.

The most prominent of the Japanese firms driving this investment is Marubeni. There has, however, also been strong investment from Osaka Gas and Tokyo Electric Power.

As the Australian energy industry moves toward renewable technologies, it appears that these firms are also targeting investments in renewable generation assets. Some major areas of investment include the following:

Traditional Electricity Generation:Marubeni through Marubeni Power Systems and Energy Infrastructure Investments 20 has invested in the Smithfield Energy Facility. They are one hundred sixty megawatts, natural gas. Marubeni has also invested in the Millmerran Power Station. They are eight hundred forty megawatts, coal-fired.

In addition, Marubeni has invested in Daandine Power Station. They are twenty-seven megawatts, coal steam gas. Lastly, Marubeni has invested in the Mt. Isa X41 Power Station. They are thirty-two megawatts, natural gas.

Renewable Generation: Marubeni, Osaka Gas, and Tokyo Electric Power have pursued investment predominantly in wind farm generation, with Marubeni acquiring a stake in the Hallet 4 Wind Farm in 2009. They are one hundred thirty-two megawatts.

Tokyo Electric Power 21 invested in the Hallet 5 Wind Farm. They are nearly fifty-three megawatts. Coonooer Bridge is nearly twenty megawatts.

Electricity Network Infrastructure: Japanese investment in Australia’s electricity network infrastructure has been limited to the acquisition of interstate interconnectors. Marubeni acquired the Murraylink Interconnector.

This connects Victoria and South Australia, with capacity of two hundred twenty megawatts. They also inquired the Directlink Interconnector in 2008. This connects Queensland and New South Wales, with capacity of one hundred eighty megawatts.

Investment in Gas: There has been substantial Japanese investment in the Australian gas industry. This has spanned large investments in liquefied natural gas, including INPEX Corporation’s investment in the Icthys gas project investment to pipeline infrastructure.

It also includes investments by Marubeni in the Telfer, Nifty Lateral, and Bonaparte pipelines. Lastly, it includes investments in the AllGas Gas Distribution network.

3. Australia Lessons Learned

Lessons learned in Australia are in many respects similar to those in the other geographies we have addressed:

Managing regulatory change and its attendant risks is a core competence: This has certainly been the case in Australia, as well as the U.S., U.K., and Mexico. It will no doubt apply in Japan as well.

Stick with a good thing when you find it.To date, the majority of Japanese investment in the Australian energy sector has been in gas or liquefied natural gas projects and electricity generation assets. These are areas which may see further expansion and privatization activities in the Australian market. 22

Cross-pollination of skills is a good thing. As noted, several companies such as Marubeni have made investments in widely different assets across the electric power value chain. They have also invested in a wide variety of upstream and downstream bits of energy infrastructure.

The skills learned from one set of assets can typically be transferred to other lines of business. This is through standardized policies and procedures, seconded staff, executive rotations, and the like. While synergy is an overused term, it might rightly apply to managing a business across newly competitive energy markets.

Implications for Japanese Companies

What does all this mean for Japanese companies as they prepare for increased competition in Japan? The lessons learned draw on several decades of experience and many billions of dollars in investment worldwide.

They provide extremely valuable guidance for success in newly-liberalized energy markets almost anywhere, including Japan. But they are merely suggestive and not exhaustive or definitive.

Beyond that, they do not constitute a full-fledged business strategy for re-entering the home market, building new lines of business, and successfully competing for customers and profits.

These issues will be addressed in the third and final installment in this series of articles about Japan, in a forthcoming issue of Public Utilities Fortnightly.

Endnotes:

1. This is one of many examples where multiple Japanese companies partner in U.S. energy investments.

2. Now it appears that Sumitomo has agreed to sell its stake in Desert Sunlight.

3. There are, however, exceptions. Mitsubishi, through its Diamond Generation subsidiary, and Sumitomo, through its Perennial Power generation subsidiary, operate some of the plants they own.

4. The operation and maintenance business tends to be less volatile than the independent power producer business, especially when the independent power plants are partly or fully operated on a merchant basis.

5. It was not until 2006 that Itochu began to acquire U.S. independent power producers, through Tyr Energy.

6. While these operations and maintenance providers tend to be independent from their parent companies, we note that Itochu’s Tyr Energy sometimes partners with its North American Energy Services subsidiary on the operation of Tyr’s plants.

7. No Mitsubishi advanced pressurized water reactors are currently under construction or in operation.

8. The one other utility in Mexico, Luz y Fuerza del Centro serving the Mexico City area, also state-owned, was closed down by the government in 2009 and subsequently absorbed into CFE.

9. Self-supply in this context refers either to power plants co-located with load, or to plants located-remotely that contract with a load.

10. Retail rates will be regulated for basic service customers. Transmission and distribution subsidiaries will remain regulated monopolies.

11. At least so far, the long-term auctions are for the basic supplier to procure energy, capacity, and clean energy certificates. At present, CFE is the only basic supplier, but the law allows for others. Clean energy certificates are produced by renewable plants. Suppliers are required to obtain certificates annually in a pre-determined percentage of their load, starting with five percent in 2018. Importantly, all renewables are on a level playing field. For example, there is no carve-out for solar, as there is in certain other jurisdictions.

12. Capacity is produced basically by a plant being available to produce and deliver energy during ex-post critical hours.

13. NERA analysis of the 2015-2029 PRODESEN (the Mexican government’s program of development for the national electricity sector).

14. NERA analysis of the 2016 Annual Energy Outlook of the U.S. Energy Information Agency. Globally, the current trend, which is expected to continue, is for historically slow growth in electricity consumption, due to continued increases in energy efficiency.

15. While this section focuses on the electricity sector, Japanese companies such as Mitsui have also invested in the Mexican natural gas sector, pipelines, liquefied natural gas regasification terminals, and liquefied natural gas long-term supply agreements, where CFE has been the off-taker.

16. But for the recent reforms of the power sector, the only options for independent power producers after contract expiration would have been be to sell directly to large consumers, or to sell to CFE. With the reforms, the producers will now have additional options when their contracts expire. They can also sell to competitive suppliers or to marketers, participate in medium term auctions, or try the spot market. The first independent power producer contracts with CFE will expire in 2025.

17. This chart does not include investments under other modalities, including build-lease-transfer or self-supply arrangements.

18. Investments made before the 2014 law are grandfathered under those arrangements.

19. The Big Six includes Centrica, Scottish and Southern Energy, Scottish Power (Iberdrola), RWE npower, E.On, and Électricité de France.

20. Energy Infrastructure Investments is a joint venture between Marubeni (just under fifty percent), Osaka Gas (just over thirty percent), and APA Group (just under twenty percent). EII holds a number of assets in its portfolio including electricity transmission, gas pipeline, gas generation, and wind generation.

21. Tokyo Electric Power has made investments in Australia through Eurus Energy, a joint venture with Toyota Tsusho (forty percent Tokyo Electric, sixty percent Toyota Tsusho).

22. It is expected that Endeavour Energy and Western Power will be privatized in some form over the next few years.

Lead image Earth images: NASA, Blue Marble, Visible Earth

Category (Actual):