Electric utility mergers loom as the next step in restructuring.

Mark C. Beyer is chief economist of the New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (NJ BPU). This article expresses his views and not necessarily those of the NJ BPU, its commissioners, or its staff.

Despite the cost advantages enjoyed by large producers, at present the electric utility delivery system resembles a "cottage industry," consisting of many relatively small firms. Mergers and acquisitions of electric utilities, in which smaller companies combine to form larger ones, have been noticeably lacking.

Yet under a true rationalization of the industry, mergers would be expected to play a role similar in effect to electric industry restructuring. Mergers would produce benefits in terms of more efficient and effective organizations, resulting in increased productivity and as a consequence lower prices. And given the large size of the electric utility industry, the macroeconomic gains could be substantial.

Why have we not seen more electric utility mergers?

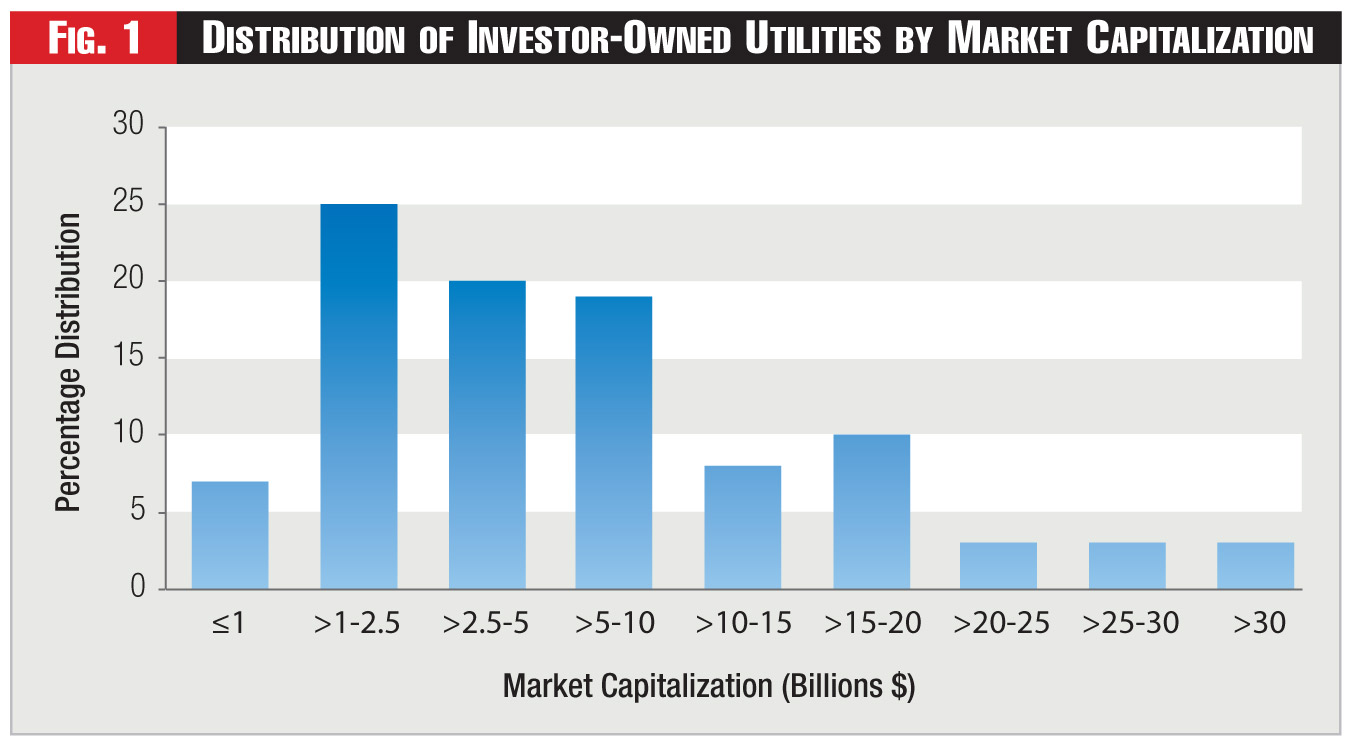

In fact, the electric utility industry in the United States is comprised of a large number of relatively small firms most of which were formed years ago based on factors such as geographic boundaries, legal concerns or political considerations, but usually not based on economic efficiency. The graph labeled "Distribution of Investor-Owned Electric Utilities by Market Capitalization" (see Figure 1) will illustrate this fact. It is based on data from the Edison Electric Institute and includes data on United States based investor-owned utilities.

Figure 1 shows that approximately 45 percent of the companies have a market capitalization of between $1 billion and $5 billion. That's a size very much suitable for a merger or an acquisition by private equity or an infrastructure or sovereign wealth fund. Approximately 20 percent of the companies have a market capitalization between $10 billion and $20 billion - a size suitable for a merger of equals with another electric utility or an acquisition by an entity such as Berkshire Hathaway.

Even though not every company would be available to merge, the current structure of the electric industry (which is primarily comprised of relatively small firms) is not economically efficient. Given the large overall size of the electric utility industry, consolidation of the industry resulting in better resource allocation and lower prices for utility services has the potential to materially increase income, output and economic growth.1

Impediments to Consolidation

There are two primary reasons for this lack of consolidation - why the industry has tended to maintain its current inefficient structure:

• The pricing mechanism, known as cost of service, which has prevailed in the industry for many years; and

• Regulatory protectionism, with effects similar to trade protectionism.

The first factor, cost-based regulation, sets prices based directly on the costs of the regulated firm. It is meant to produce prices that would exist in a properly functioning market. Rate of return regulation, the predominant form of cost-based regulation, establishes the return on equity a utility can earn.

Depending on the jurisdiction, the rate of return on equity can be used to set rates initially, as a cap with earnings above the cap returned or shared with ratepayers, or as a guarantee with rates adjusted upward if necessary to enable the company to earn the approved return. The objective is to ensure that prices are set at a level that allows the utility to provide service and invest appropriately in new facilities, but not so high as to allow excessive profits. A fair return on utility investment, although not guaranteed, is reasonably assured through the rate-making process. Cost-based pricing does not necessarily produce rates for utility services that are efficient, least cost, or beneficial to the consumer. Markets are much more efficient at allocating resources and determining prices; however, cost-of-service pricing limits their effectiveness.

The second factor is what we might term "regulatory protectionism." Regulatory and trade protectionism both refer to policies that restrict or restrain trade or competition, and thereby retain relatively inefficient producers in the market. The reasons for such protectionism may be varied, but they include a desire to retain local control, as well as a misunderstanding as to the benefits of creating more efficient companies (perhaps because the benefits are poorly explained by the merging companies).

While regulatory protectionism may appear beneficial in the short term, in the long run, such barriers are counter-productive. They create less efficient firms and retard productivity gains. Nevertheless, bigger utilities (e.g., Duke Energy) are more efficient and effective enterprises, just as Home Depot is a more efficient and effective enterprise than the local hardware store. Regulatory protectionism leads to higher prices plus an inefficient use of resources.

Restructuring Benefits

In recent years, approximately one-half of the states in the United States have adopted some level of deregulation or restructuring of the electric utility sector designed to enhance competition and eliminate inefficiencies in the supply market. The goal of restructuring was to increase competition in both wholesale and retail markets in order to reduce electric rates and expand consumer choice; consumers did not want to pay for excess capacity and utility inefficiency.

Utility generation was required either to be divested or transferred to an unregulated subsidiary. The cost of energy and capacity was eliminated from the retail rate such that retail suppliers could compete directly in supplying electricity to the consumer. Electricity would be bought or sold in the wholesale market either through an auction process or through bilateral contracts. In contrast to efforts to expand electricity supply options, transmission and distribution would continue to be regulated under traditional cost of service regulation.

Restructuring eliminated cost-of-service regulation in generation and replaced it with a system of prices and markets that allowed producers to keep the profits from efficiency gains in electricity generation. After all, cost-of-service pricing had imposed the majority of cost overruns on captive retail customers, providing few incentives for production efficiency or technological innovation. The economics of rate-regulated utilities are such that the larger the rate base, the greater the earnings and the higher the stock price. This regulatory paradigm tends to encourage excessive capital spending: utility earnings are determined largely by the size of the rate base, which does not encourage the efficient allocation of capital.

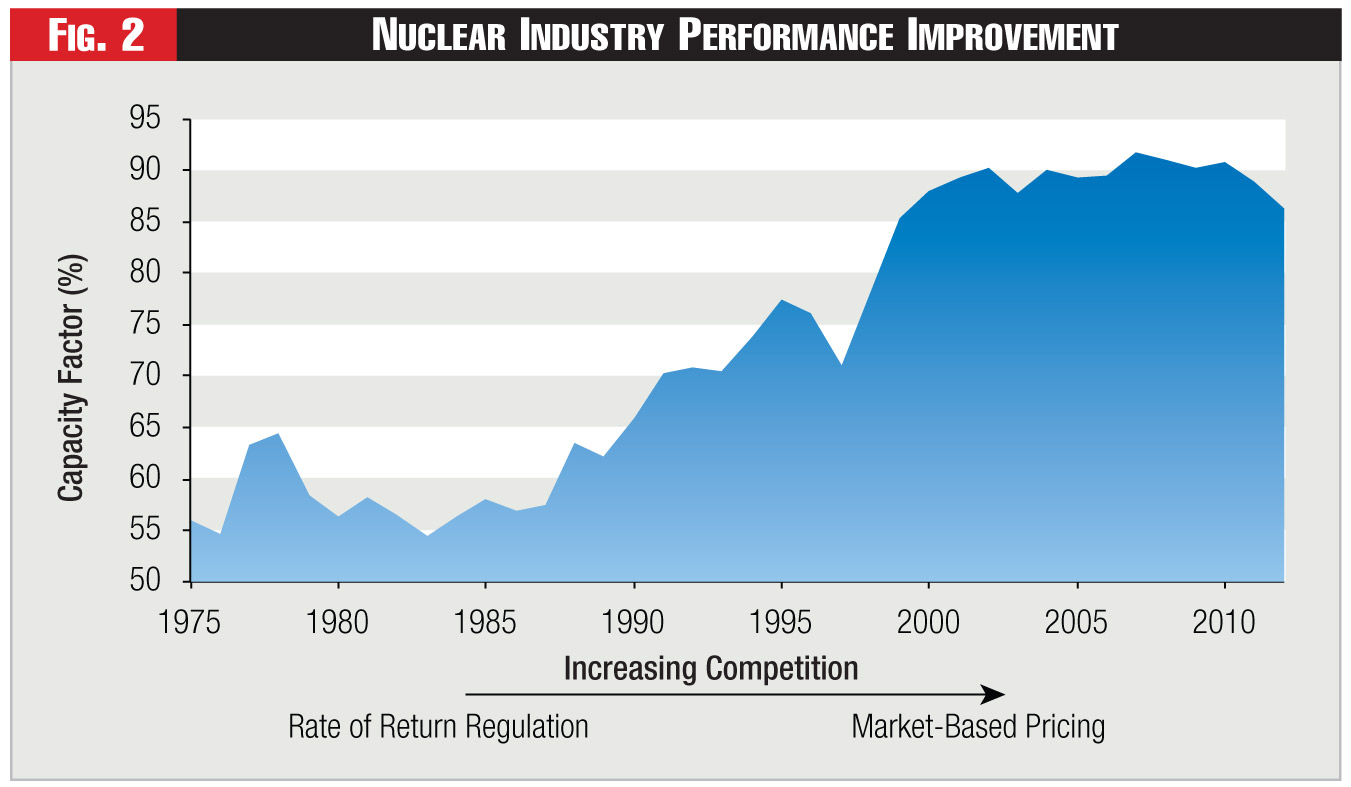

In contrast, if investments are made outside the utility, the incentive is to minimize costs, so as to maximize profits. The profit incentive resulted in a dramatic increase in capacity factors at existing coal and nuclear plants. The efficiency gains were especially pronounced at nuclear plants as can be seen in Figure 2.

Prices for utility services based on the low capacity factors that were commonplace prior to restructuring appeared reasonable and cost-based at that time, despite the fact that the prices are not reasonable when compared to the prices determined by producers operating in competitive markets. Prices determined by competitive markets are often much lower than prices thought to have been reasonable under regulation. Although restructuring has produced dramatic productivity increases in generation, similar productivity increases have not been realized in transmission and distribution.

Merger Benefits

Mergers of electric utilities can provide numerous benefits to both ratepayers and shareholders, similar to those that have come from industry restructuring. Mergers can create the large organizations with economies of scale that can provide utility services in an effective and efficient manner. New technologies such as smart grid and advanced renewables can save costs and create environmental benefits; yet producers need volume to spread the costs of these complex and expensive fixed assets.

That the benefits of the merger must exceeds the costs - including the cost any premiums paid by the acquiring company - underscores the need for effective execution of the merger plan to assure that all stakeholders benefit. Only an adroit management team can fully realize the synergies; it requires much more than simply combining two organizations and eliminating redundant costs. The lower cost structure provides additional funds for investment in rate base without an increase in prices, further increasing profitability and shareholder value.

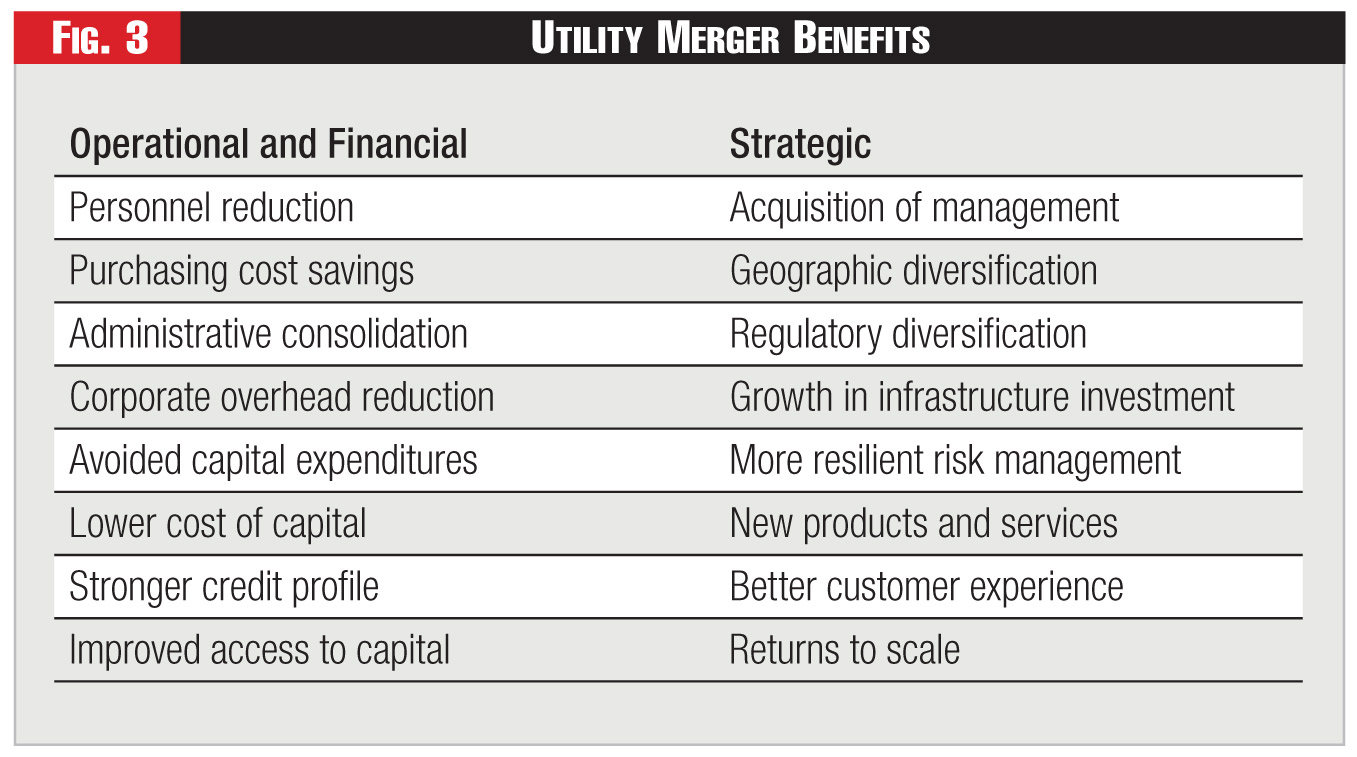

Mergers of electric utilities can lead to significant cost savings through personnel reduction, purchasing efficiencies, administrative consolidation, reduction in corporate overhead, avoided capital expenditures, lower cost of capital, stronger credit profile and improved access to capital, and streamlining of data processing functions. In addition to cost savings, mergers may yield other important benefits, such as the acquisition of management, geographic and regulatory diversification, opportunities for growth in infrastructure investment, more resilient risk management, new products and services, acquisition of skills (i.e., nuclear and data processing expertise), better customer experience, returns to scale, etc. More importantly, over time, all of the factors of production can be adjusted to optimal scale, further reducing costs and improving the overall efficiency of the organization. (See Figure 3.)

In the longer run, large, highly efficient utilities will produce lower rates for consumers and higher returns for shareholders. Profitability and shareholder wealth increase relative to the status quo as inefficient firms are not rewarded in the market. The lower cost structure could be used to finance additional energy efficiency or renewable investments without raising electricity prices to the consumer. Conversely, small, parochial producers cannot produce either competitive rates for consumers or adequate returns for shareholders.

Likely Merger Candidates

Mergers are most beneficial among distribution utilities and among vertically integrated (distribution and generation) companies that are subject to rate of return regulation. Mergers among companies with regulated distribution and unregulated generation are less beneficial. That's because investors value regulated assets at a higher multiple of earnings and because potential market power concerns factor into the regulatory decision-making process. In addition, competition has already led to greater efficiency in unregulated generation markets, reducing the potential for further savings.

Furthermore, inherent conflicts exist in a holding company structure that contains both a distribution utility charged with providing safe, adequate and proper service at a regulated return, and a generation company seeking to maximize profits in competitive markets. In this type of situation, investors can always seek to maximize profits through a merger where the unregulated generating affiliate is spun-off, sold or merged with another unregulated generation company. And that is true especially if the holding company contains diversified investments that also could be sold or spun-off. History shows that diversified investments traditionally produce substandard returns based on the axiom: it is hard enough to make money in a business you understand, but almost impossible to make money in a business that you don't. And even when diversified investments are successful, such success usually is not reflected in the price of a company's stock.

In addition, some financial observers believe that investors prefer "pure play" securities, such that shareholder value would be increased if there were separate distribution and generation companies, especially when the generation company operates in competitive markets. The thinking goes that traditional utility investors prefer the earnings stability associated with the ownership of regulated assets rather than the higher risk and higher return associated with competitive markets. In this view, merchant generation affiliated with utilities could be pulling down the valuation of the parent company, making it a propitious time to sell, merge or spin-off the unregulated generation.2

Regulatory Approval

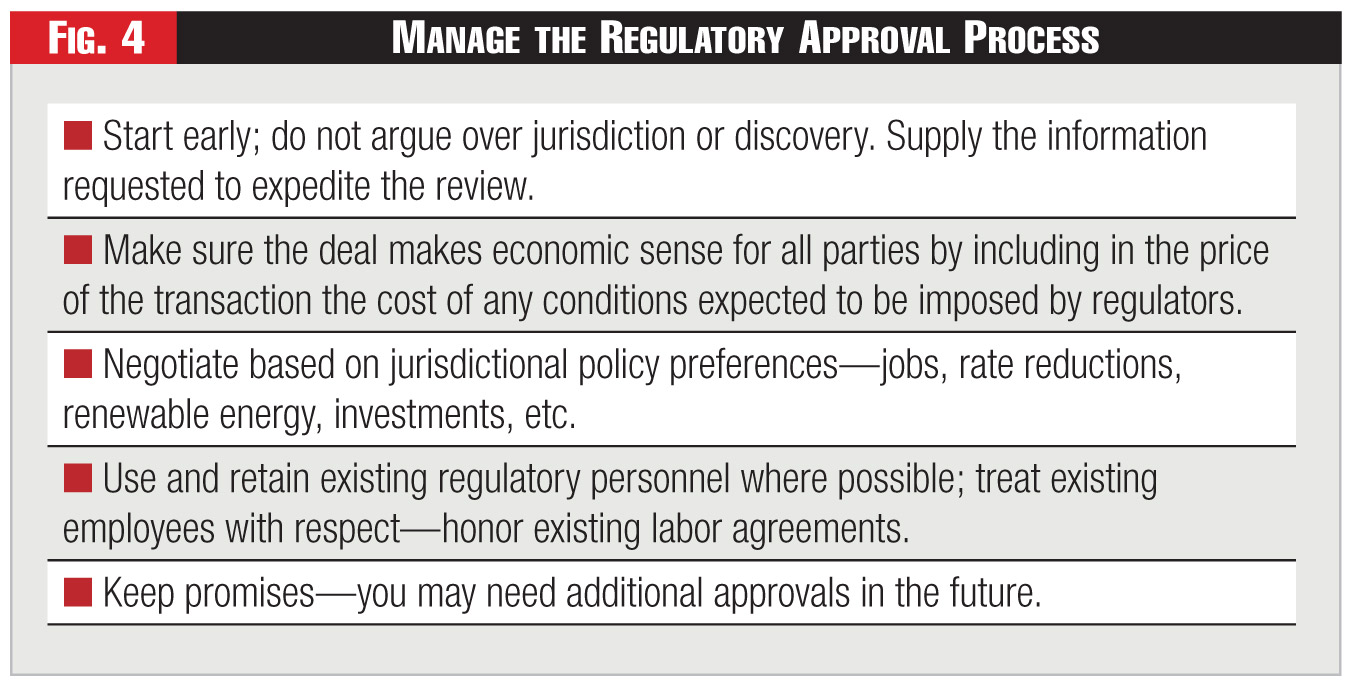

The need for regulatory approval may account for the lack of mergers, either by imposing costs, or causing utility management to shy away from certain deals if regulatory approval appears too difficult to obtain. Nevertheless, numerous mergers have been approved that preserved economic benefits for both ratepayers and investors.

Thus, the decision as to what degree of jurisdiction to exercise with respect to mergers ought to depend on the nature, scope and relative riskiness of the particular transaction and its impact on customers and other parties. The focus of the review should be to not micro-manage the affairs of the company or its affiliates, but to assure a fair allocation of the costs and benefits between ratepayers and shareholders.

Most jurisdictions require that the transaction must produce positive benefits, or else produce no harm. However, the difference between these two ideas - the positive benefits test versus the no-harm standard - appears to be more form than substance.

In both cases, cost/benefit analyses provide guidance as to the desirability of the proposed transaction. Under the positive benefits test, the expected benefits must exceed expected costs for the transaction to be approved, while under the no-harm standard the expected benefits can be equal to or exceed the expected costs for the transaction to be approved. In other words, only in the case where the expected benefits are equal to the expected costs do the two standards produce different conclusions. From a practical viewpoint, there is no significant difference between the positive benefits test and the no-harm standard. However, states that do not review and approve mergers frequently lose out by not having a seat at the bargaining table.

State commissions evaluate mergers based on statutory criteria such as the impact on (1) competition, (2) rates, (3) employees and (4) service quality. The evaluation process provides a forum for stakeholders such as employees, unions, public advocacy groups, ratepayers, environmental organizations as well as debt and equity investors to have input into the process, which leads to greater public confidence in the decisions that result.

Let's consider these four criteria in detail.

1. Impact on Competition. The concern here is to what extent a combined entity would have the ability to influence the market price of electricity. Market power refers to the ability of a firm to raise the price of electricity above levels that would prevail in a competitive market. Even a market distortion of one, two or five percent could cost consumers hundreds of millions of dollars for a large utility. Available evidence indicates that power markets are often less competitive post merger.

Whether a merger of utilities that own generation will raise market power issues depends on whether the generation assets are regulated. Market power is less of a concern in cases where electric utilities are vertically integrated and prices are based on rate of return regulation. If the generation assets are subject to cost of service regulation, the matter can normally be resolved with behavioral mitigation and consideration of future entry and exit. If the merger involves unregulated generation assets where the merged company will have a significant share of the market, such that market power could be exercised, expect considerable regulatory intervention including possible divestiture of assets. Market power would affect not only the price paid by merged companies' customers but also the customers of all other utilities which buy power in the wholesale power market.

Mergers that lead to higher electricity prices as a result of market power are generally difficult to get approved, even with significant concessions. A large increase in the price of electricity harms residential customers, particularly low-income consumers. Higher electricity prices weaken overall industrial competitiveness and retard economic growth; expect strong opposition from large power users. Horizontal mergers of distribution companies make the most economic sense and encounter the least regulatory resistance.

2. Impact on Rates. A merger should produce a reduction of costs at all levels of the company - particularly at the corporate level, where various departments such as investor relations and communications can be reduced or eliminated. These "synergy savings" are estimated by the company and its consultants, argued over with regulators, and ultimately split between ratepayers and shareholders with 50 to 75 percent going to ratepayers, presumably in the form of lower rates.

The goal is to develop a reasonable estimate and split such that the basic economics of the transaction remain intact. Unrealistically low estimates of merger savings are counter-productive to the approval process. So, too are assertions that all the savings will occur in the non-regulated portion of the business, and therefore cannot be passed along to ratepayers. Adroit management will estimate synergy savings and include such cost sharing in the initial pricing of the transaction.

Nevertheless, despite considerable regulatory scrutiny, company management skilled in integrating new companies frequently exceeds the initial estimates, which benefits the company only until the next base case, when rates are reset based on the cost of service. And it's important to note here that the reset rates tend to be lower than the rates would have been without the merger, thereby further benefiting the consumer. Incorporating regulatory incentives for efficient behavior and technological innovation into the rate setting process will help to ensure that the benefits from economies of scale are fully realized and reflected in the prices charged to customers.

An important related question is the mechanism by which the synergy savings are returned to ratepayers. An immediate bill credit has a high present-value cash cost without necessarily being appreciated by the recipients. Other uses of the synergy savings including new call centers in the service territory particularly if jobs are returned from offshore, enhanced severance packages for employees which are especially attractive to older workforces close to retirement, new office buildings or green energy projects, may have lower cash costs but higher public appeal. Any base rate cases should be filed and settled prior to the merger. A merger followed by a large base rate request will likely prove unsalable.

The rate impact issue usually includes a thorough review of multiple issues, such as (a) the financial management of the company, (b) money pool and ring fencing questions, in the case of a multi-jurisdictional holding company, and (c) dividend policy consistent with the maintenance of investment grade credit ratings, etc. All equity transactions preserve credit quality and the merged company can buy back stock at a later date depending on cash flow and credit metrics. Complicated transactions that only financial professionals can evaluate may receive a poor reception from individual investors.

3. Impact on Employees. Job reductions occur mostly at the corporate level, in such staff areas as personnel, investor relations, legal, corporate finance, etc. Line operations are much less impacted. Yet any loss of jobs, although unfortunate, is not likely to have a significant long-run negative impact on the state's economy. In the longer term, the benefits from lower-priced utility services contribute to regional economic growth far exceeding any initial loss of jobs.

Nevertheless, the review process does include determining potential job loss, and making sure the employees are treated fairly (and in the case of multi-jurisdictional mergers, that each state bears a proportionate share of the costs and benefits). Some mergers have been structured such that an extremely small minority of individuals becomes rich leaving other employees to defenestration. Such an approach assures that almost every employee, whether manager or craft, will be working against the transaction.

Other general areas of concern involve honoring union contracts, adequacy of pension funding and review of actuarial reports, and retention of adequate personnel to perform regulatory functions. It is strongly recommended that the acquirer retain existing regulatory personnel who possess knowledge that is difficult for outsiders to duplicate except over a long period of time.

4. Impact on Reliability. The maintenance and improvement of service quality is also generally considered in the context of the merger, especially with utilities experiencing service quality issues. Service quality encompasses such standard reliability measures as Customer Average Interruption Duration Index (CAIDI) and System Average Interruption Frequency Index (SAIFI) as well as OSHA based safety measures. Performance on such measures may be compared with other utilities, and the use of financial penalties and rewards may be considered. Additional regulatory oversight may be required to assure appropriate allocation of resources within the holding company structure.

The issue of reliability generally depends on the quality and reliability of service prior to the merger. And because many transactions involve holding companies with operations in multiple jurisdictions, those states that have a review process are better able to advocate for additional investment, service quality improvements and jobs. In the case of companies that already provide high-quality service, the concern lies with any possible future deterioration. In the case of companies with a poor record on reliability, a major selling point of the merger may be the improvement plan presented by the acquirer, which may include detailed engineering and financial commitments.

In all cases, the public must be assured there will be no deterioration in service quality. Call center performance is frequently considered in this context, as is restriction on the future location of call centers. The adequacy of financial and manpower resources dedicated to operations are also part of the review process.

Why Consolidation Will Win

The smart money should bet on a rise in mergers in the electric utility sector. And here's one key reason: the electric industry today shows parallels with other American industries that have lately seen their fair share of restructuring and consolidation.

The impetus for the change includes continuing pressure from deregulation, rising investor expectations, increasing capital requirements, declining allowed returns on equity, new entrants into the market, and slow revenue growth.3 The lack of revenue growth is the result of economic weakness, increased energy efficiency, net metering and falling natural gas prices.4 Some of these pressures are cyclical but others appear to be secular in nature. Even where there is no direct competition in the provision of services such as with distribution and transmission suppliers, competition among buyers which use those services as inputs in the production process creates pressure to reduce costs and lower prices.

Market forces and technological change have caused the consolidation and restructuring of numerous industries in the United States. IBM's hegemony was shattered by the personal computer while Digital Equipment, Prime, Wang and many other computer companies did not survive. Wal-Mart's efficiency in distribution produced a list of casualties in retail too numerous to mention. Large pharmaceutical companies have merged to maintain earnings growth because of patent expirations and a paucity of successful new drugs. The railroad industry has become much more efficient through restructuring and consolidation. The wireless telecommunications industry continues to consolidate as have the chemical and oil industries.

Increasing transparency and intense competition throughout the economy assure that high cost producers cannot survive when lower cost alternatives exist. Once profit margins decline and/or markets for products become commoditized, industry consolidation frequently results because only large, low cost producers can create shareholder value in low margin businesses.

For all these reasons, consolidation in the electric utility industry is inevitable as customers demand better products at lower prices. The continuing need to reduce costs, enhance competitiveness and increase shareholder value will lead to further industry consolidation despite cost of service pricing and regulatory protectionism. Electric utilities are characterized by low revenue growth; cost cutting and a low level of revenue generating investment do not produce significant earnings growth and stock price appreciation. Mergers can have a salutary impact on earnings growth, innovation, investment, rates and shareholder value as a result of economies of scale, better resource allocation and lower cost structure.

Endnotes:

1. Developing a list of merger candidates is beyond the scope of this paper, however, a merger between Consolidated Edison, Inc. and Public Service Enterprise Group, Inc. would have the potential to produce synergy savings, lower rates and fund innovation in distribution and transmission which could produce extraordinary benefits for both ratepayers and shareholders.

2. This discussion is not meant to imply that merchant generation is an inferior business just that investors value the business based on different metrics, and that competitive businesses require different management and financial skills to maximize shareholder value.

3. Well capitalized new entrants such as Google or IBM in energy management or smart grid could negatively impact utility revenues while large, well capitalized entrants such as oil companies could invest downstream in generation which would erode energy and capacity revenues in merchant markets but could maximize the value of their gas assets.

4. The impact of low natural gas prices on merchant generation is important as even some nuclear plants are having trouble recovering fixed costs in markets where prices are determined based on marginal costs. In addition, low gas prices encourage distributed generation thereby depriving distribution utilities of revenue especially if combined with net metering.

- - -

Lead image © Can Stock Photo Inc. / javarman

Category (Actual):