Many Deals Completed, What Have We Learned?

Tom Flaherty is a partner with Strategy& – a part of the PwC network – who has focused on utility growth strategy, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and business transformation for over forty years. He has been involved with approximately eighty percent of utility M&A stock transactions greater than a billion dollars in the U.S., and supported clients in Great Britain, Italy, Spain, France, Argentina, Venezuela, Australia, and Canada in consolidation or carve-out assignments. He has also provided expert testimony in more than thirty jurisdictions on utility combinations and benefits.

Over the last twenty years, the U.S. utility sector has gradually dwindled. The power sector shrunk by approximately sixty percent, from ninety-five to just under forty companies. The gas sector shrunk by an equivalent percent, from just over fifty companies to right at twenty.

Numerous other companies tried to consolidate, only to find that striking and concluding a deal is hard, notwithstanding the industrial logic that underpins the combination. Yet, this experience gained over the last two decades of consolidation activity has been a wise teacher to the industry.

Both successful and failed deals have been instructive to utility managements on whether and how to position a proposed transaction for pursuit and approval. These lessons from the front - whether related to competitive, value, regulatory or execution experiences - provide valuable insights to those companies considering their first combination. As well as to those companies pursuing further scale-up.

Successfully incorporating these lessons into future deal planning can help merging companies avoid both time delays and adverse outcomes.

Consolidation in Perspective

Reducing the scale of both the power and gas sectors by approximately sixty percent in just twenty years is not just an outcome linked to the unique strategies of a host of prior deals. Rather, it is a product of the utility industry's rapid evolution to a point where consolidation is no longer viewed skeptically, but is widely expected and keenly awaited.

Lesson 1: Industrial Logic Continues to Evolve

In the mid-1990s, the utility industry landscape looked nothing like what we see today. Utility service territories often were interlaced across geographies, leaving the visual of a balkanized industry. Thus, early day combinations were keen to leverage the most obvious of rationales: contiguous service territory.

Managements believed that close proximity enhanced the chance to provide increased scale to weather imminent competition, leverage brand reputation, and maximize deal synergies.

These initial transactions focused on creating a larger company of common assets within a logical footprint. It didn't take long, however, for companies to consider that the greatest strength to withstand competition, besides low costs, was to have more customers to serve.

Thus, the convergence of electric and gas combination companies began to occur. With more customers to serve, more services to offer, and less possibility of encroachment, broader offering potential could yield greater revenues and enhanced customer loyalty.

A logical notion that the industry still seeks to realize today.

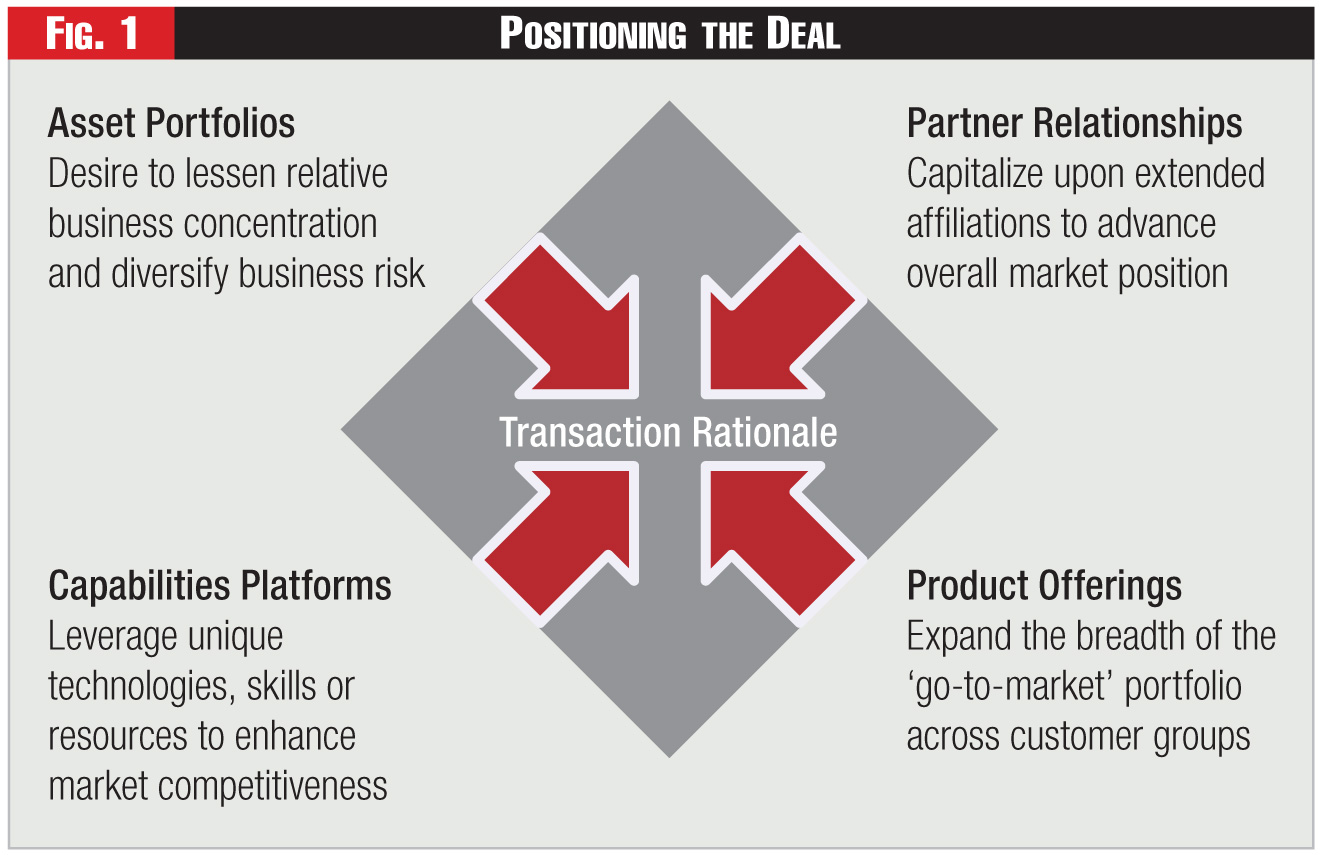

Merging companies today often rationalize their transactions as predicated on positioning and platforms. The evolution of distributed technology makes alternative supply of generation available to all classes of customers and causes companies to focus on understanding emerging technologies, sub-markets, and customer behaviors.

This need is leading to the desire to fill gaps in capabilities, such as positioning, through experiences, skills, relationships and arrangements that may be maintained by a potential merger partner.

See Figure 1.

With the expected shift towards gas-based sources of supply, companies are also placing a greater interest on related resources, such as pipelines, storage, reserves and basins. These assets are now viewed as valuable platforms for further expansion and value.

Now the industrial logic for recent deals has evolved beyond proximity and optimization to leverage and growth.

Lesson 2: Geographic Proximity No Longer Matters

Utilities recognize that the industrial logic for a transaction is closely scrutinized and business coherence is highly valued and expected by the markets and regulators. But in a shrinking industry, and with many sector earnings growth rates more in the four to five percent range than in the six to eight percent range of just a few years ago, companies are challenged to find attractive merger partners or acquisitions.

This scarcity of partners has led to electric and gas cross-over deals. But it has also expanded management horizons beyond natural borders and obvious candidates. Many transactions now are comprised of partners that would not have looked likely ten years ago.

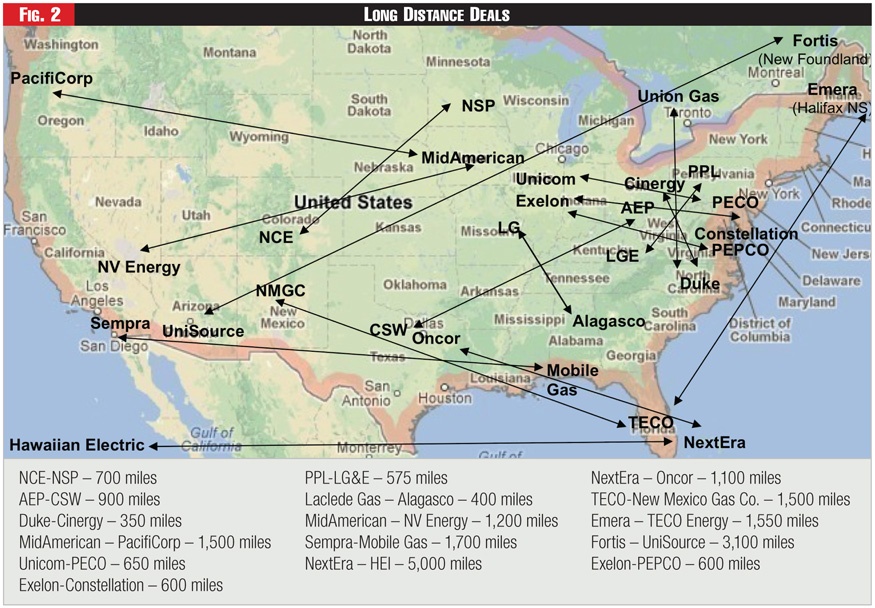

In fact, almost half of the last twenty non-financial buyer transactions have been announced by companies with headquarters more than five hundred miles away from one another. This affirms the rationale of several notable predecessor combinations that expanded management thinking on what deals could make sense.

SeeFigure 2.

The era of proximate transactions ended around 2000 with the emergence of cross-region deals that often brought two bookends together. These early forerunners proved that companies could manage across distance and that synergies could travel.

No artificial constraints existed that would limit the natural integration of many corporate functions, nor of business unit support functions. Governance processes could be successfully extended and physical and virtual integration was possible across much of the business.

This early experience has led to recent transaction conduct over even broader geographies, some stretching thousands of miles. When companies propose combinations that extend across multiple time zones, it naturally captures the interest (and sometimes the scorn) of industry pundits that question this industrial logic.

But distance does not totally undermine the benefits available from combination. In an era of increasing positioning and platform objectives, distance can actually advance strategic outcomes through portfolio strengthening.

With the long and sustained history of utility combinations over the last twenty years, the Monday morning focus is no longer on unexpected press releases, but on whether the market's expected next logical transaction is announced. The shrinking industry has conditioned observers to expect more transactions. The focus has moved to who rather than whether.

Value in the Deal

For decades, potential synergies levels have been headlinesin deal press releases as companies touted a primary rationale for undertaking the combination. Companies acknowledged the obvious. Consolidation could unlock future value and reduce costs through avoiding duplication and overlap and capturing economies of scale.

Lesson 3: Synergies are Attainable

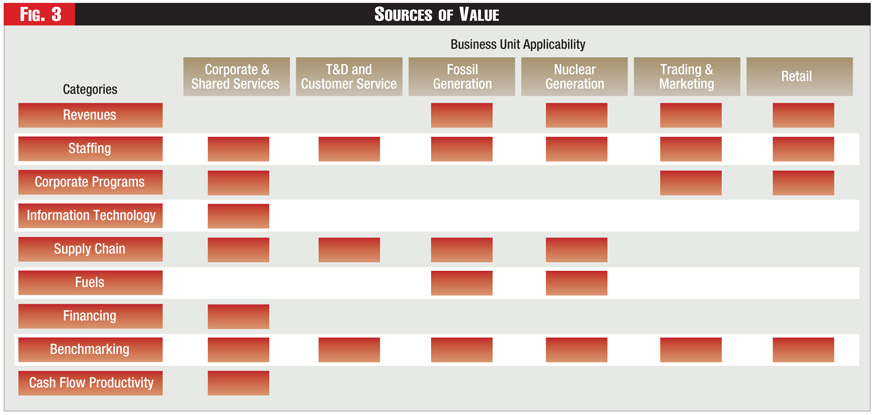

Synergies have been a primary outcome from combinations with estimated cost savings averaging approximately eight percent of total combined non-fuel operations and maintenance expense by the time steady state was achieved. Although this number can vary depending on the relative scale of the companies.

And, cash flow savings can be even greater as several synergies categories contribute capital expenditure, fuel or financing cost reductions that are sizable in their own right.

See Figure 3.

More impressively, utilities have had much more success in realizing estimated savings than their industrial counterparts. Most industrial deals contain some promise of revenue synergies from new markets, products or customers, which required betting on top-line growth which is the least controllable management lever in a transaction.

And this new revenue was expected from companies that may have only been tangentially aligned, meaning their purpose was to create something new.

Conversely, electric-to electric or gas-to-gas utilities transactions are fully operationally overlapping, with almost no difference in fundamental composition other than generation fuel sources.

Given this high degree of structural and operational commonality, it is not surprising that the utilities sector has consistently hit its targets for identified synergies realization. While industrial companies often find that revenue expectations are overstated and under-achieved.

The fact that the utilities industry has successfully demonstrated the ability to capture expected synergies has favorably influenced how Wall Street views transaction announcements. Effective synergies realization supports the expected rationale for most transactions and illustrates management prowess in deal execution.

Lesson 4: Value Extends Beyond the Quantifiable

But many other value sources were realized in these prior deals, both qualitative and quantitative. Often discounted, the value of scale is a significant benefit from consolidation, but not just because bigger is better.

The value of scale lies in enhanced flexibility rather than size for its own sake. There is no question that scale provides access to opportunities that may have otherwise previously been foreclosed. And scale provides an ability to weather disruptions to cash flows.

However, the value of scale is best reflected through the additional flexibility possible to companies from having greater financial strength and capacity, whether for financing, investment, market positioning, or strategic purposes. This flexibility enables acquirers to leverage more options than other less financially sufficient companies. As well as to sustain market strategies when challenges emerge.

Prior combinations also have added value in several other areas that contribute to the strategic positioning of the acquirer: broader value chain participation, addition of new capabilities and greater market diversity.

All of these areas can enhance the nature of other potential synergies that may be available. And each independently can add unique forms of value, such as new investment (value chain), go-to-market execution (capabilities), and risk management (market diversity).

The utilities industry, and its customers and shareholders, have been beneficiaries of its prior acquisitiveness. Both the rate of cost growth and actual cost levels at the time of the transaction declined as a result of completed transactions. Compared to other industries, power and gas utilities have delivered on the promise.

Regulatory Challenges

Despite the industry's success in financially and operationally executing combinations, transacting utilities have always felt a high degree of trepidation about their pursuit. Companies have been (and remain) skeptical about what kind of regulatory outcome would be received and whether the benefits attained justified the risks assumed.

And managements are justified in worrying about the regulatory outcome. After all, no one wants to expend nine to twelve months of effort only to see their transaction fail due either to unrelated regulatory agendas, inequitable benefits sharing, or intrusive financial "look-throughs" that can have adverse capital structure impacts.

Lesson 5: Most Regulatory Decisions Are Equitable

However, the regulatory track record on deal approvals over time has been good and savings sharing outcomes have been acceptable, when regulators actually get to inspect them. Compared to the late 1990s, few deals do not ultimately receive approval. Moreover, regulatory commissions have maintained close to fifty-fifty sharing of synergies in cases where they were presented.

It is clear that regulatory commitments and conditions required in every deal have become more demanding, limiting or expensive. But these are simply the price of admission. Most requirements have not been onerous and many are simply acknowledgement of what already exists in practice with the regulator, such as dividend restrictions, commission notice, etc.

Other conditions, such as headquarters retention, minimum employee levels, etc., are more directed and stringent, but not unduly restrictive. And other commitments, such as maintained charitable contributions, increased low income assistance, etc., are relatively small in comparison to the levels of synergies and value inherent in the transaction.

Admittedly, recent approvals have been challenging and often looked unattainable based on public sentiment and regulatory posturing. But managements persevered and overcame table stakes issues related to public benefits (or no harm) standards, employee treatment, and reliability preservation. They also successfully dealt with non-deal issues, such as renewables commitment, grid modernization, and generation policy alignment.

Lesson 6: Benefit Clarity Drives Regulatory Decisions

In some recent cases, however, regulators have been asked to approve the transaction without any submission of quantifiable benefits to customers. The logic of late has been that the simplest way through a transaction process has been to not talk about cost savings that could come at the expense of local jobs.

Companies have used a range of rationales for this approach. These stretch from there are no synergies, to any synergies will automatically flow through in the next rate case, to let's just negotiate an outcome.

This approach leaves regulators in a position where they either have to look past their own state approval standards, ask for a specific synergies study to be filed late, or impute a level of savings to the transaction. All of which have happened in recent deals.

These options leave the merging companies in a higher risk position regarding decision timing and ultimate approval, compared to a more standard approach of filing quantified benefits up front.

In several recent cases, the transaction timeline was either stretched out for an extended period and or benefits stipulation was one-sided and the companies were hostage to an open ask with no ceiling.

In several of these transactions, the level of imputed savings became the focal point for approval. An escalating bid was necessary to overturn a transaction disapproval decision and rescue the deal. These filing strategy decisions unintentionally exposed the merging companies to a higher level of approval risk than necessary.

Lesson 7: Approval Timeframes Are Shrinking

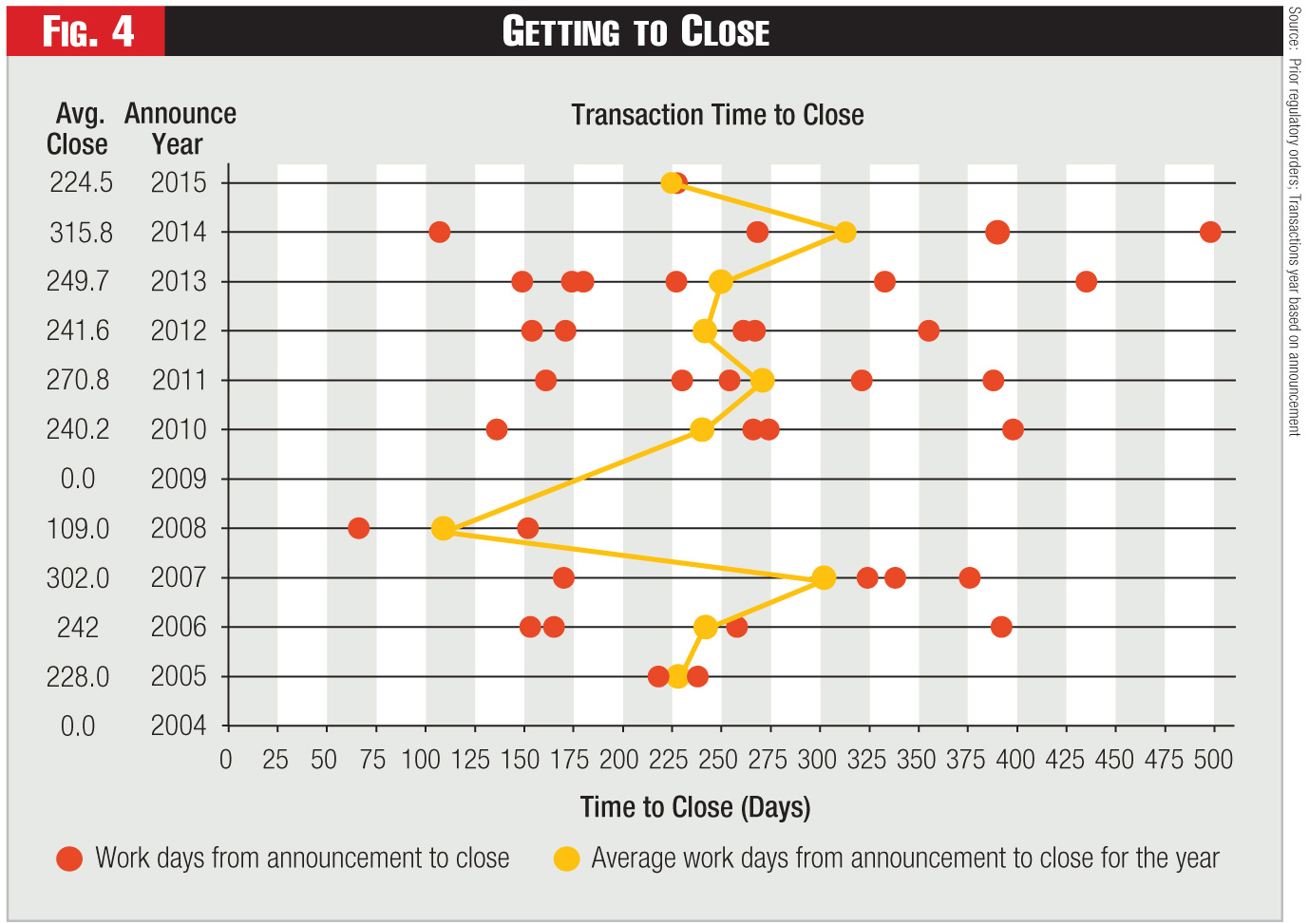

Since regulators have become more familiar with utility combinations, approval timeframes have generally stabilized and shortened. Unless the filing strategy itself created delay due to the need for more complete information, or isolated agendas became linked with the transaction approval process.

Average transaction timelines since 1995 have generally contracted from approximately sixteen to eighteen months, to approximately eight to nine months. Commissions have also become more specific about the merger standards they will employ.

See Figure 4.

Transaction approvals are also accelerating as companies more aggressively pursue settlements, given the focus on meeting more explicit standards.

Some isolated transactions have extended into the plus or minus eighteen-month window from filing to approval. These transactions generally were extended by the lack of benefits demonstration, hostile reactions to transaction structures, or FERC market power issues that emerged.

Multi-state transactions will normally see the longest approval durations given the range of issues involved across the regulatory agencies. Transactions that also involve nuclear plants or tight generation markets also can see extended timeframes. Logically, single state convergence mergers generally see the shortest schedules.

The shrinking of deal approval timeframes is an important outcome that can influence how companies consider possible transactions. Knowing that the companies will not be held hostage to an extended unpredictable approval duration relieves the fears of management that they will sit in regulatory purgatory and miss future strategic opportunities.

Post-Close Execution

While utilities have little direct control over how regulators will respond during the deal approval process, they have full control over what happens after transaction close: actual integration and post-close operations. Many companies conduct this stage of the deal lifecycle very well. However, ultimate integration success hinges on how aggressively management chooses to define and pursue integration.

Lesson 8: Integration is the Hardest Part of the Deal

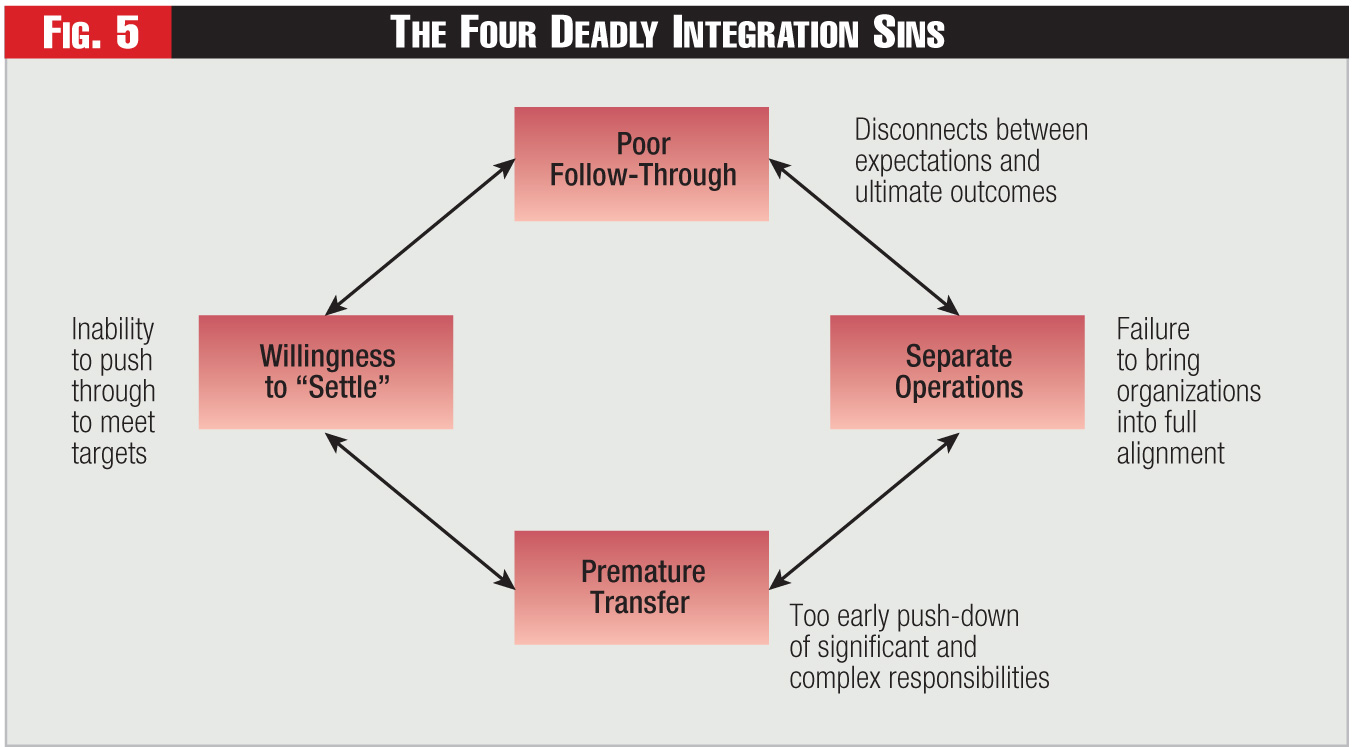

Managements are often lulled into believing that once the deal is negotiated and approved the hardest transaction chore has been completed. This is a common fallacy, even when merging companies have experience from a prior transaction. If management does not get this part of the deal process right, then it can saddle the combined business with challenges that can take years to unwind.

See Figure 5.

While the negotiation and regulatory processes may seem like they have been challenging in their own right, the real work begins when the deal actually closes. And this is when those least involved in the deal become responsible for the most demanding part of the transaction.

Integration is hard because the process requires substantial work to be done in a timeframe when each company still understands very little about how each really operates. It is also difficult as it forces managements to make decisions about how to operate before they may be ready to define these outcomes.

These factors challenge companies to place their bets on strategies, technologies, processes, and people with much still to learn about their partner. Success post-close is highly dependent on how the merging companies philosophically approach integration.

If they believe that business simplicity is a cornerstone, then they will seek to fully integrate as quickly as possible. Conversely, if they believe that a single operating model is not required, then they may pursue separation as a better solution.

One of the above models will typically prevail when deal economics matter. The other will be adopted when less change is viewed as advantageous to avoid disruption.

Lesson 9: Early Starts Make a Difference

Given the challenges above, it makes sense for managements that decide to integrate fully to do it rapidly. Success here lies in taking advantage of the available time window provided by the approval process.

As illustrated earlier, the average regulatory approval process extends for approximately nine months. This provides ample time to conceive, plan and execute a fulsome integration process, even if there is uncertainty over many decisions in the near-term.

We have found that rapidly and fully utilizing this nine-month window pays dividends to the buyer immediately. The process creates a forcing function for cooperation where cross-knowledge is minimal.

It also jumpstarts the countdown to post-close operations and brings focus to what it takes to achieve a well-defined and low risk Day-1 close. Perhaps the greatest value lies in the ability to quickly move toward joint operations rather than to remain separate for an extended period of time.

This outcome benefits the post-close company operationally as roles and responsibilities are established. It benefits it financially as available synergies can be more quickly captured and value from the deal accelerated.

The early start to integration enables the management team to focus internally on bringing the companies together rapidly. But it also enables the refinement or reconstruction of the going-forward strategic plan and path to growth. While the companies cannot actively execute together during the approval pendency, having a clear view of priorities serves them well post-close.

Lesson 10: Always Finish the Task

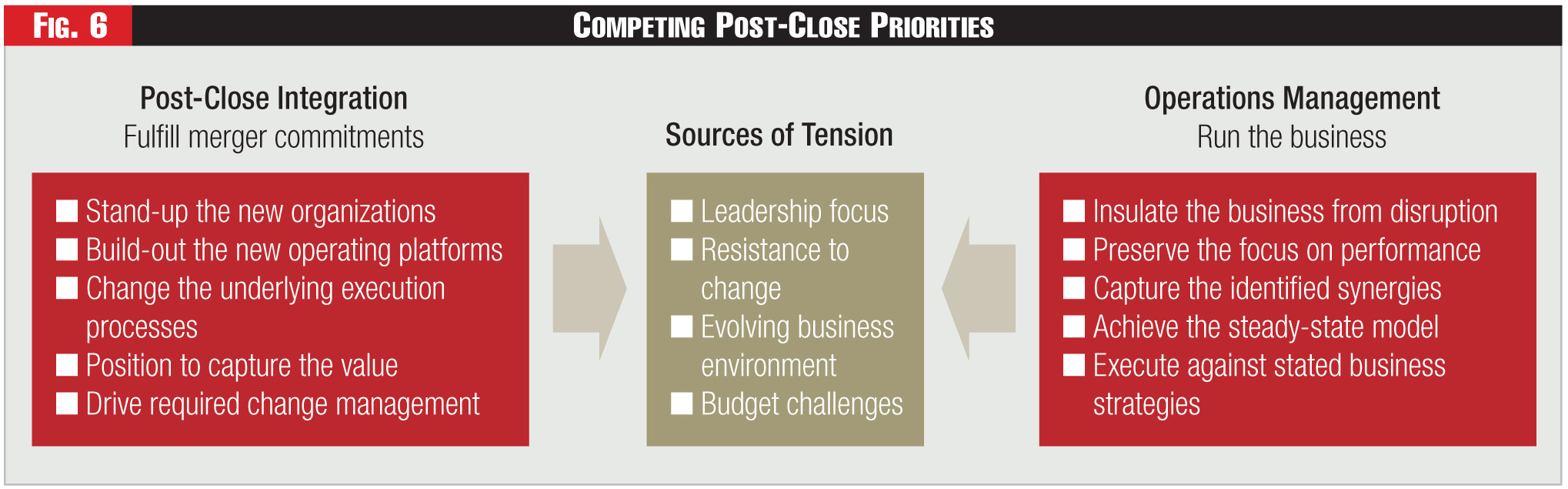

It is tempting to declare victory once the approvals are received and Day-1 close is addressed. But this would expose the merged company to unnecessary operating risk and create potentially adverse shortfalls to outcome attainment.

Once the deal closes, the transaction and integration teams can believe their work is done and hand the remaining work over to the business and functional managements going forward. But at close, nothing has actually been integrated. It's only been planned. It may take still several years to successfully complete.

Totally disbanding the integration teams often leads to several adverse outcomes: stalled momentum, decision rethinking, conflicting priorities and lost value, among others. This can cause conflict between transaction and operational objectives.

See Figure 6.

Better to leave the integration process in-place, though refocused, than to take the risk that months of good work could be undone by a desire to devolve ownership of actions prematurely.

These challenges to integration success suggest that managements recognize that finishing the job is fundamental to success. If retaining more formal ownership or oversight of continued integration enhances the attainability of post-close operations success, then these outcomes will have been worth the extra effort expended by management.

The last twenty years of utility combinations have set a tone for the shape and pace of future consolidation. The industry cannot replicate what has transpired in this past timeframe. But it can leverage this body of knowledge to position future transactions for successful outcomes. And it can avoid many of the challenges that prior transactions experienced as they forged a new industry direction.

Category (Actual):